Understanding Technical Analysis

24 November 2008, Financial Times

A key reason investors have lost a lot of money in this broad market collapse is because they simply watched as prices of ostensibly strong, sound companies dissolved in front of their eyes, convinced that after each sharp decline, the next move had to be up.

One way to avoid getting caught in this trap is through the use of technical analysis. This perspective bases investment decisions on the price action of securities, largely eliminating sentiment and subjectivity from the selling process. As a result, decision-making is far easier, especially during a sell-off that can paralyse investors and wipe out wealth.

In a nutshell, technical analysis assesses the supply and demand for a stock based on price movement and market sentiment. So when a stock breaks down past a support level established by its previous trading behaviour, technical analysis would provide a sell signal well before fundamentals.

This is especially useful when the market is indiscriminately destroying value across sectors and national markets. In this context, “technical analysis becomes an even more essential tool for preserving wealth”, says Louise Yamada, a former technical analyst at Citigroup for 25 years who now runs her own investment advisory firm in New York.

With many portfolios having already lost nearly half their value, some investors may think it is too late to benefit from this strategy.

But Ms Yamada says the current environment, with deflationary characteristics and interest rates falling to low levels, has parallels with the Depression.

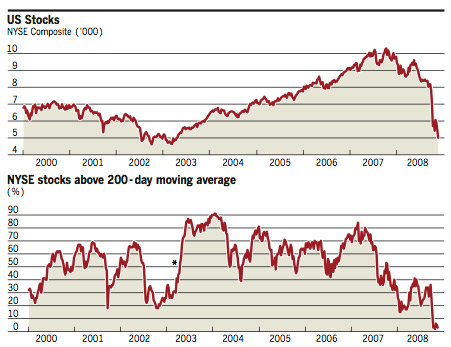

She observes that the price action of the Dow Jones Industrial Average between 1932 and 1938 closely matches that of the New York Stock Exchange Index between 2002 and 2008.

Ms Yamada then specifically looks at the movement of stocks starting in September 1929. Equities initially declined 35 per cent then rallied in the following spring, making up nearly half their losses.

The percentage of NYSE stocks above their 200-day moving averages remains deeply damaged. * The ultimate crossing over the 50 per cent level in 2003 confirmed the more structural technical ‘buy’ signals. Today the sustained weak reading demonstrates that there is not enough evidence to support a market reversal.

Louise Yamada, technical analyst

“But it was the second wave of selling that followed that wiped out investor wealth,” she says. By the middle of 1932, the market was down 89 per cent. She believes that if investors had properly read the price action of the market when it broke down past the initial low set at the end of 1929, they would have realised there was worse to come.

This example helps explain the role technical analysis can play in gauging the integrity of market trends.

Phil Roth, chief market analyst at the New York brokerage Miller Tabak, was dubious about last year’s rally that brought the Dow to a new record high, breaking past 14,000 in early October. “Measured against the 2,000 stocks of the New York Stock Exchange the move was narrowly driven with less than 10 per cent of the listed companies making new highs,” he says. To Mr Roth, the thinness of the run-up was indicative of a rally that was running out of steam and is typical of how a market tops out.

Trend reversal was confirmed when the Dow sold down past 12,000, a support level that had been first tested in February 2007 and then again in March this year. “This increased the risk that the market could then descend toward 10,000,” Ms Yamada says, “and when that level was broken, there was greater risk of another 1,000 point drop.”

Mr Roth admits he initially misread the pullback, thinking it would be an average sell-off. But when he saw NYSE trading volumes spike to record levels from an average of 4.9bn shares a day to 6.6bn in September, he knew he was witnessing what he calls a “killer bear”.

Selling peaked in mid-October when the trailing 10-day average daily trading

volume hit a record 7.9bn shares, with unprecedented volatility. The Chicago Board Options Exchange volatility index, known as the Vix, which normally trades around 10, hit 58.

Gail Dudack, who runs her own research advisory firm in New York and has been tracking markets both fundamentally and technically for more than three decades, points to another disturbing technical measure: the huge spreads between prices and their 200-day moving averages. This year on October 27, the spread on the Dow hit 30.5 per cent. The last time it gapped wider was in November 1937 when the fig- ure reached 31.4 percent.

However, technical analysts are not suggesting investors should dump all their holdings. Most technicians know their findings are inherently defensive, which in normal markets can stop investors out of subsequently profitable positions when a correction is misread as a trend reversal.

But their findings can help investors better interpret the road signs, especially when stocks break below their existing support levels for more than a few days on high volumes. If that happens, then investors could well see further erosion of their portfolios.

On the bright side of today’s dismal market, if the current trading range the market has established holds, it could be creating a base. After the S&P 500 lost more than 20 per cent in the first week in October, breaking below 8,500 on October 10, the market could be seen forming a bottom. Over the past month, the index has been trading within a defined bandwidth. According to Ms Dudack, “the longer this base holds, the greater the likelihood that the worst of this nightmare could be over with the next substantial market move being up”.

But she readily admits it is far too early to tell if that is what is happening. Every bear market is different. Historical bear market averages, such as maximum duration, volatility, volumes, and price spreads to moving averages, that define the nadir of past sell-offs, are only guideposts.

Technicians agree that several months of lower, less panic-driven trading volume, reduced intraday price volatility, followed by a strong broad-based breakout on higher volumes are required before they can be sure that today’s range-bound trading is indeed a bottom. “When this occurs,” says Mr Roth, “it may mean we have seen the worst of the crisis regardless of the status of credit default swaps, hedge fund liquidations, and government bail-out programmes”.

But Ms Yamada thinks a turning point is probably still some distance away. “We are seeing 12 of the Dow 30 blue chip companies, including Microsoft, GE, and Citigroup, breaking below lows set during the last bear market,” she says.

Moreover, these companies barely participated in the 2003-07 rally, suggesting the current trend is a continuation of the 2000-02 bear market. If she is correct, a quick turnaround is probably not in the offing.

Leave a Reply

Warning: Undefined variable $user_ID in /home/globa525/public_html/wp-content/themes/eric_theme/comments.php on line 59

You must be logged in to post a comment.

GIR's Investing in the New Europe

GIR's Investing in the New Europe